DePaul University/Jeff Carrion

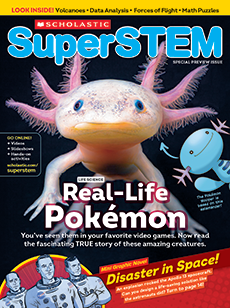

Kenshu Shimada

Skye Basak is up to her elbows in mud. After hours of digging, she pries loose a stone, revealing a shark tooth that’s 16 centimeters (6 inches) long. A tooth that big could be from just one shark: a giant prehistoric one called a megalodon!

Basak is a fossil hunter who runs a company called Palmetto Fossil Excursions in Summerville, South Carolina. She often shares the fossils she finds with a local museum for research. Megalodon teeth are some of Basak’s favorite fossils to dig up. They can be three times as large as those of great white sharks!

Kenshu Shimada is a scientist at DePaul University in Chicago who studies fossils to learn about prehistoric life. In recent years, he has used megalodon teeth, like the ones Basak finds, to better understand this massive fish!

Skye Basak is up to her elbows in mud. She’s been digging for hours. She lifts a stone and sees a shark tooth. It’s 16 centimeters (6 inches) long. That’s really big for a tooth! It could only come from one shark: a giant that lived long ago. It was called a megalodon!

Basak is a fossil hunter. She runs a company called Palmetto Fossil Excursions. It’s in Summerville, South Carolina. Basak often shares the fossils she finds with a local museum. Megalodon teeth are some of Basak’s favorite fossils to find. They can be three times as large as great white shark teeth!

Kenshu Shimada is a scientist who works at DePaul University. It’s in Chicago. He studies fossils to learn about ancient life. He’s uses megalodon teeth, like the ones Basak finds, to learn more about this huge fish!